CEO of Art Finance and Group General Counsel Freya Stewart was recently invited to speak at the STEP Bermuda Webinar Series: Art Finance.

In the session, Freya demystified Art Finance, including discussion on: what types of collectors use Art Finance and for what purposes; what the key commercial terms are; and the eligibility and execution process. Freya specifically touched on how and why Bermuda based clients, and Trustees globally, use The Fine Art Group’s Art Finance services, together with relevant case studies from The Fine Art Group’s loan portfolio. Finally, Freya offered insights into current issues in the world of Art Finance and the year ahead.

WATCH NOW THE STEP BERMUDA WEBINAR

PART II: ART FINANCING TODAY

The Fine Art Group is proud to present The Expert’s Perspective: A Three-Part Series, produced in partnership with Risk Strategies.

Over the coming months, The Fine Art Group will be releasing a three-part series exploring the current market, the increasing popularity of Art Finance and the art of pricing Fine Art.

Hear from the experts on the current themes from the world of art finance. This event will demystify the process and uncover what lies ahead in the art lending industry.

Further Reading

- Spear’s Magazine Lists Philip Hoffman & Freya Stewart as Top Professionals in Art Advisory and Art Finance

- Artnet Art-Secured Lending Brokerage Program

“Bank of America suggested investors seek out funds like the Fine Art Group, Classic Car Fund, and the London International Vintners Exchange Fine Wine Fund Index (FWIFFWID), in addition to REITs and commodity funds if they’re looking for real asset exposure.”

In a recent note, Bank of America’s chief investment strategist, Michael Hartnett, reports that real estate, commodities, and collectibles could outperform stock market returns over the next decade.

Hartnett notes that real assets are a more overlooked part of the market that may offer investors protection against inflation while diversifying their portfolios, which is why he encourages investors looking for real asset exposure to seek out funds such as those offered at The Fine Art Group.

To read the full article, and to learn more about Michael Hartnett and Bank of America’s advice to the smart investor, please click here.

PART I: ART MARKET UPDATE

The Fine Art Group is proud to present The Expert’s Perspective: A Three-Part Series, produced in partnership with Risk Strategies.

Over the coming months, The Fine Art Group will be releasing a three-part series exploring the current market, the increasing popularity of Art Finance and the art of pricing Fine Art.

Please join our Senior Art Team as they provide a timely and informative market analysis following the March auctions in London and other recent public and private transactions.

WATCH NOW

Further Reading

- The Asking Price: Understanding Value 1

- Morgan Long Speaks with Barron’s About Guaranteed Works at Spring 2023 Auctions

- Guy Jennings Speaks With The Art Newspaper

23rd March saw the first major evening auctions of 2021 following an unprecedented year of upheaval and change. The auction houses attempted to centre their sales around the March London calendar slot, albeit later, in an effort to restore the old schedule. Upon the eventual announcement of the timeline for the loosening of social controls, Phillips decided to delay their 20th Century and Contemporary sales to mid-April to allow for more ‘In person’ viewings for their sales. Sotheby’s and Christie’s chose to continue with their schedule which meant private collectors were unable to physically view the sale but art trade were. In keeping with the houses’ ever creative approach to our current situation, on some occasions they opted to bring works to local collectors, to help stimulate as much pre-sale interest as possible given the circumstances.

All of the houses opted for mixed category evening sales, perhaps a signal insert that they struggled to get consignments, however, not a trend we see declining, having long been in play before Covid. The Leonardo sale at Christies being a key turning point, it is a fantastic stimulus for other areas of the market, including Old Masters and Modern British, that lack the same marketing budget and often command less global attention. The strategy paid off in both cases. Sotheby’s Modern Renaissance sale, with artworks from 1500 to present day, totalled £81.6 million (hammer) against a presale estimate of £60- 86.5 million and 87% lots sold. Whilst Christie’s totalled £100.5 million (hammer) against the presale estimate of £66.6 – 96.7 million. Also further bolstered by a £40.4 million (hammer) sale total from Olivier Camu’s Surrealist sale, traditionally held this time of year.

The mixed category format facilitated some extraordinary prices for artists not traditionally included in the evening sale setting. Notably a new record for British sculptor Frank Dobson whose work rarely comes to auction. The female torso which once belonged to Alberto Giacometti, surpassed its estimate of £250,000 to sell for £2.04 million (including premium), smashing the 2005 record of £338,500 (premium). Czech artist František Kupka, known for his association with Kandinsky and Malevich also reached a new record of £7.55 million (including premium), tripling the low estimate.

Despite March usually being a London slot, both houses decided to spread their sales across multiple locations, in keeping with the international relay style auction approach developed last year. Sotheby’s held a Paris Impressionist and Modern auction before the London sale, in an effort to mirror the volume offered by Christie’s with their Surrealist sale. Totalling €30.4 million above the presale estimate of €19.3 – 28.9 million, the sale was a remarkable success with 91% lots sold. The relay tactic, stitching Paris evening sales to marquee auction calendar moments, seems to be attracting significant global bidding. To attest to the interest in the Sotheby’s Paris sale, the London sale start time was delayed due to the high volume of bidding in the Paris segment, with even in person room bidding for a Renoir sculpture with harked back to an almost immemorable time. The most notable result was €13.1 million (premium) for an 1887 Van Gogh canvas, against an estimate of €5 – 8 million, acquired by the Reuben family. Despite the slight hiccup with a phantom online bidder, the work saw bidding from New York, Paris, London and Hong Kong, proving that Paris is a solid stage for major lots.

72 x 48 in. (183 x 122 cm.). Sold for HKD 323,600,000 in We Are All Warriors: The Basquiat Auction on 23 March 2021 at Christie’s Hong Kong.

Christie’s also opted to hold a one lot Basquiat Hong Kong auction, despite technically being taken by Jussi Pylkkänen from the rostrum in London, the sale was indeed in Hong Kong dollars. Belonging to collector Aby Rosen, the 1982 warrior painting saw three bidders from New York and Hong Kong compete before it went to Jacky Ho in Hong Kong. It was a solid indicator of the continued appetite Basquiat, this latest result marked a $30 million profit on the seller’s 2012 investment; also providing positive foundations the forthcoming 1982 Versus Medici painting to be sold at Sotheby’s in New York in May, estimated to fetch between $35 – 50 million.

The Christie’s consignment hammered within estimate at HK$280 million ($36 million) or HK$323.6 million ($41.8 million) including premium, which ultimately beat the recent Richter, to become the most expensive piece of Western art sold in a Hong Kong auction. The success of the lot was a sign of the continuing strength of the Asian market off the back of seventeen records at Christie’s December Hong Kong auction and Art Basel’s recent Art Market report confirming China overtook the US to become the largest auction market in 2020. Significant Asian bidding on roughly a quarter of the lots across the sales attested to this and to make sure these sales remained accessible to global collectors these ‘evening sales’ were in fact held at 1 and 3pm respectively to allow for more social hours.

The Banksy market showed no signs of slowing with a new auction record at Christie’s for a painting donated to Southampton hospital, sold to raise fund for the NHS. The work hammered for a staggering £14.4m hammer (£16.76 million with premium) against an estimate of £2.5 – 3.5 million and was chased by six bidders before selling to Tessa Lord’s client on the phone. Sotheby’s also reached an extraordinary price for a signed edition of Girl with Balloon selling to an online bidder for £1.2 million (premium). Despite being catalogued as an artist proof edition of eighty-eight, it belongs to a wider edition of 150, and an unsigned edition of 600, and speaks to extreme level of demand for Banksy at the moment. Interestingly, these works saw no US bidding with collector interest based solely in the UK or Asia.

In demand primary market artists also continued to see the most spirited bidding with several artist’s auction debuts selling for well beyond their estimates. Despite Issy Wood’s ‘auction debut’ in fact taking place the day before with a successful result via Loic Gouzer’s fair warning app, herself alongside Joy Labinjo, Amoafo Boako, Claire Tabouret, as well as continued demand for last year’s breakout auction star Matthew Wong all ignited the early parts of the sales.

An overall sense from the last few auctions was that bidding was thin for lots at higher price points and from more traditional or established segments of the market. And whilst this rang true for some pieces from these sales, including a Francis Bacon selling on just one bid at £4.3m with a rumoured estimate of £8-12m, several lots did extremely well. Perhaps reflecting that collectors feel more confident transacting at these price levels now the art market has weathered the past 12 months and there is some light at the end of the tunnel. Two major Picasso paintings at Christie’s both sold significantly above their last auction results. Works by Fautrier saw serious bidding across both houses, with Christie’s reaching a new record and Olly Barker at Sotheby’s taking some twenty minutes over a 1966 painting which sold for nearly quadruple the high estimate to Martin Klosterfelde’s client for £3.1 million (premium).

Other high prices included Edvard Munch’s Embrace on the Beach, which sold for £16.3 million (premium) to a Hong Kong client, above a £12 million high estimate and an Arshile Gorky landscape, Garden in Sochi, set to sell for a high estimate of £2.8 million, instead it sold for £8.6 million to Bame Fierro March’s client.

These results proved encouraging for the first marquee moment of the year for the art market. The three-month gap certainly helped build appetite and demand. The continued lack of physical art fairs works in the favor of the auction houses, the sheer size of their organizations has allowed them to tour major artworks, arrange delivery for physical viewings and remain open for trade which has offered them a significant advantage to the now monotonous experience of an online viewing room. As the year progresses it will be interesting to see if this level of bidding will be sustained but with such solid infrastructure in place to conduct these global sales with ease, there is an overwhelming sense that the location of sales is no longer a barrier to bidders. Collectors are attracted to the works no matter where and this yields excellent results as they continue to capture the interest of the international collector base.

Image 1: Image courtsey Sotheby’s; Image 2: Image courtsey Sotheby’s; Image 3: Image courtsey Christie’s; Image 4: Image courtsey Christie’s; Image 5: Image courtsey Sotheby’s; Image 6: Image courtsey Sotheby’s

Further Reading

“A lot of our clients are entrepreneurs, and they use leverage across their businesses and personally,” said Freya Stewart, CEO of art finance at The Fine Art Group. “They have a lot of valuable capital tied up in their art collections and they want to release that capital for other uses.”

Following a surge in loan requests due to the pandemic, Freya Stewart discusses the appeals of leverage to entrepreneurial collectors who are using their artworks as both loan collateral and an investment product.

To read more of Freya’s comments in this CNBC article, please click here.

The Fine Art Group are proud to announce that our Founder & CEO Philip Hoffman has been selected as a Top Recommended Art Adviser in the 2020 edition of Spear’s 500.

As a leading wealth management authority, their annual publication is an essential guide to the market’s best private client advisers, and we are thrilled to be recommended to their UHNW and financial services community.

To learn more about Philip Hoffman and The Fine Art Group in the 2020 Spear’s 500 rankings, please click here.

“Gathering people together at art fairs created so many discussions and opportunities. We need that oxygen.”

Following the news that Art Basel is to be postponed once again, Managing Director Guy Jennings discusses the recent absence of art fairs and the snowball effect this has on gallerists and auction houses.

To read more of Guy’s comments on this piece by The New York Times, please click here.

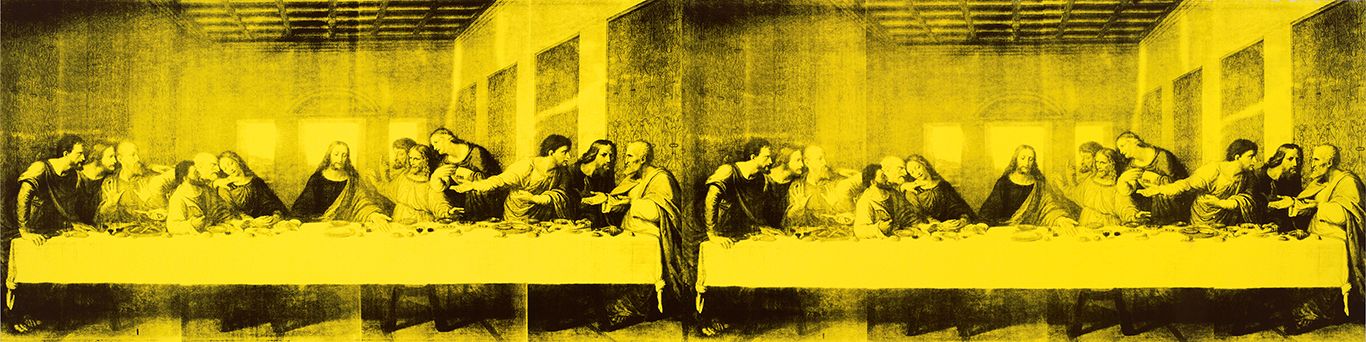

The art trade on both sides of the Atlantic has been abuzz with sales from permanent collections at public institutions, otherwise known as deaccessioning. Most prominent in the recent debate about associated ethics is the Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA). The institution offered major works – by Brice Marden (3, 1987 – 88), Clyfford Still (1957-G, 1957) and Andy Warhol (The Last Supper, 1986) – for sale at Sotheby’s in October 2020 with a combined estimate of 65 million USD. Just hours before the Marden and Still paintings were due to hit the block (the Warhol was to be offered privately), the museum withdrew both from the auction in response to a growing maelstrom of negative criticism, internal and external.

The BMA was technically operating within the bounds of newly loosened regulation from the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) in America: a targeted, finite response to the ongoing pandemic which has, to all extents and purposes, obliterated gate receipts from museum balance sheets. Funds from the sale would be directed towards ongoing running costs (even though the museum was not in financial distress), ‘care of the collection’ and, crucially, new acquisitions to diversify the collection of a major museum rooted in a city with a 65% black population. The museum director had even secured public consensus from the executive director of the AAMD before proceeding with the proposed deaccessions.

Operating within the rules, with admirable objectives, the plan was still deemed controversial enough to attract bitter criticism from all sectors of the art world and, further, controversial enough to spook the institution into withdrawing the works from public sale. Why?

Long seen as one of the unassailable taboos in the UK museum sector, and generally handled with judicious caution in America, two key factors have contributed to a temporary loosening of the strict ethical codes surrounding the practice. The first is the decimation of visitor numbers to museums due to the global pandemic. The second is a growing sense of urgency, especially in American cities with black majority populations, to develop public collections which reflect the diversity of society at large.

Permanent collections housed by museums, often accumulated over decades or even centuries through a patchwork of philanthropic gifts, bequests or acquisitions, are generally intended to be just that. Caroline Douglas, Director of the Contemporary Art Society (CAS), an organisation that acquires work on behalf of their partner museums in the UK, explains: ‘Museums are the forever proposition – that’s why artists want to be in them.’ Gifts to museums, whether from an individual or an organisation such as the CAS, are usually given with the explicit proviso that such works must remain part of the collection in perpetuity.

In both America and the UK, professional membership organisations publish guidelines of best practice for their member institutions. While rules vary, there are a few broad points of consensus. Until the global pandemic, one of the most common restrictions was that works could not be sold to keep the lights on. Deaccessions – sales from the permanent collections – might be allowed where works fell outside an institution’s ‘core collection’ and with the rigorously enforced purpose of funding new acquisitions. In other words, funds raised must be reinvested back into the collection.

There is subsequently a dual aspect to the question of deaccessions: why is the work being sold? And what will the funds be spent on? Having a defensible answer for one part of this equation isn’t enough. Institutions must make a clear case for the acceptability of a sale, and there are subsequent restrictions – both written and unwritten – pertaining to the use of sale proceeds.

The risk of eroding donor confidence in the entire museum sector underpins much of the regulation at play. Not only are museums usually charities or non-profits with beneficial tax codes, they are also typically built on the generosity of private citizens and the state. Selling works from the collection – given on the explicit or implied understanding that they would remain the collection forever – is therefore seen as a grave betrayal of the trust placed in them by donors. It subsequently threatens to dismantle faith in the very mechanisms and structures which maintain museums as viable economic entities in the first place.

There is another great risk with museum deaccessions. Tastes change, fashions come and go. The world evolves. While some artists may appear utterly irrelevant to the present moment, they may come to be seen as pivotal by later generations. And what might appear frivolous and inconsequential in one historical era might be understood as prescient and vital by museum audiences of the next. There also remains – most pertinently in the case of the BMA, but generally for museums in Western Europe and America – the question of representation and the art historical canon.

It’s clear to today’s audiences that the ‘approved’ art historical account of the post-colonial age needs expansion, revision and rewriting. But it’s also impossible for anyone to know what the cultural consciousness of the future might deem important. The mission of the museum is, therefore, inherently conservative: to hold, intact, collections intended for the public good. The prevailing taste which forms a public collection is likewise, in and of itself, a historical artefact.

Similarly, selling the work of living artists can have a profoundly negative impact on their market and career trajectory. While museum acquisitions are the gold standard of validation for an artist, sale of their work from a museum, logically, can have the opposite effect. Essentially suggesting that an artist is, in the eyes of the museum (the custodians and narrators of art history) no longer of consequence. To make such a dramatic, public and negative statement about an artist’s work goes entirely contrary to what is widely understood as the Hippocratic Oath of museums vis-à-vis the wellbeing of the artistic community it serves.

2020 has shown everyone – inside and outside the art world – that systems, structures and rules that previously seemed immutable are in fact entirely contingent. Many public institutions have survived this year with furlough schemes, goodwill and inventive short term strategies. But they can’t live on vapours alone. The Victoria & Albert Museum, for example, received 15% of its usual traffic in August. Such precipitous drops in visitor numbers are untenable. Museums need donations yes, but most importantly they need an audience, gate receipts, successful gift shops and humming cafes. Another long stretch into 2021 without this revenue will bring financial distress, just as public borrowing hits record highs in the UK and the glamourous social events which generously lubricate the cogs of private philanthropy remain strictly off limits. We can therefore only foresee more – not less – works coming to market from the museum sector next year. Outcry or no outcry, reality must bite sooner or later. The debate continues.

Image 1: Image credit Sotheby’s; Image 2: Image credit Baltimore Museum of Art; Image 3: Image credit Amir Hamja/Bloomberg via Getty Images; Image 4: Image credit Katherine Hardy/The Art Newspaper; Image 5: Image credit Baltimore Museum of Art

Further Reading

- Collection Management

- When the Kids Don’t Want it: Converting Your Passion Assets into Charitable Impact

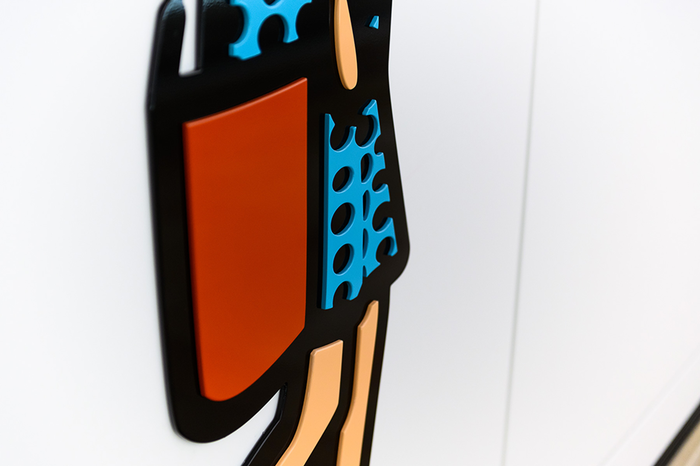

JULIAN OPIE SITE-SPECIFIC COMMISSIONS

The Fine Art Group is delighted to announce the completion of two major new, site-specific commissions by Julian Opie for Swire Properties in Hong Kong.

Parade. (2020) depicts sixty-two colourful and dynamic characters from all walks of life as they go about their daily business. The multi-layered and dimensional metal figures are finished in glossy varnish, accompanying passers-by in their journey through the pedestrian link between the Mall, Three Pacific Place and Starstreet Precinct.

Located along the walkway between the Island Shangri-La, Hong Kong and Conrad Hong Kong, Running 3. (2020) occupies a dramatic position along a prominent raised walkway. Conceived as a continuous frieze of thirteen life-sized figures in black vinyl, Running 3. embodies the dynamic of central Hong Kong.

Opie’s distinctive formal language is instantly recognisable and reflects his artistic preoccupation with the idea of representation and the means by which images are perceived and understood. Always exploring different techniques both contemporary and ancient, Opie plays with ways of seeing through reinterpreting the vocabulary of everyday life; his reductive style evokes both a visual and spatial experience of the world around us. Drawing influence from classical portraiture, Egyptian hieroglyphs and Japanese woodblock prints, as well as public signage, information boards and traffic signs, the artist connects the clean visual language of modern life with the fundamentals of art history.

The artist has commented on observing busy city crowds:

“A constant flow in both directions. Each person a mass of decisions and style and attributes with a destination and only a fleeting moment in front of me but combined, they create a constant flowing crowd. Each random person would be great to draw, better than I could ever invent.

I draw using a graphic program that allows me to bend thick lines over the photograph and fill the gaps with flat colour. A gang of characters emerges, caught in mid stride, going about their business with bags or phones or cold drinks. Their random, momentary decisions became frozen into a set piece, a logo and symbol drawn in the most emphatic and generalised way I could manage while sticking to the details of what I saw. Symbols and hieroglyphs, images and road signs perform similar tasks of turning objects and people into a language that is specific enough to describe but general enough to be read. These words can be combined to form sentences just as the people combine to form crowds. Walkways and pavements turn pedestrians into lines of text, read left to right.”

The series of figures, created for Pacific Place by British artist Julian Opie, is the latest addition to Swire Properties’ permanent art collection, as part of the Company’s long-time support of the arts and place-making. Inspired by and designed to engage with its community – the workers, shoppers of Pacific Place and people of Hong Kong Parade. and Running 3. is a noteworthy highlight for the Pacific Place community and beyond.

Find out more about the project here.

Visit www.julianopie.com to find out more about the artist and his works.

OUR SERVICES

Offering expert Advisory across sectors, our dedicated Advisory and Sales Agency teams combine strategic insight with transparent advice to guide our clients seamlessly through the market. We always welcome the opportunity to discuss our strategies and services in depth.

Image 1: Image courtesy Julian Opie; Image 2: Image courtesy Pacific Place; Image 3: Image courtesy Julian Opie; Image 4: Image courtesy Pacific Place; Image 5: Image courtesy Julian Opie